Beasts, Talking Animals, and Catholic Tradition

[Part of Ipsissima-Verba]

This page was last updated in January, 2024.

"Bless the Lord, you whales and all creatures that move in the waters, sing praise to him and highly exalt him for ever. Bless the Lord, all birds of the air, sing praise to him and highly exalt him for ever. Bless the Lord, all beasts and cattle, sing praise to him and highly exalt him for ever." (Daniel 3:79–81)

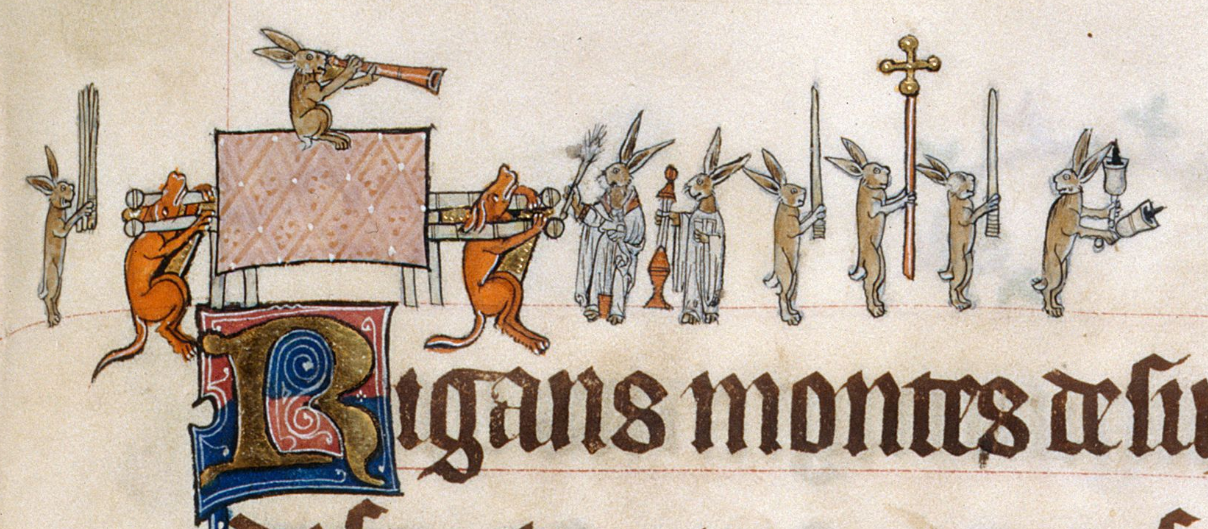

Marginal illustration from the Gorleston Psalter (1310-1324). British Library, Add 49622, f. 133r.

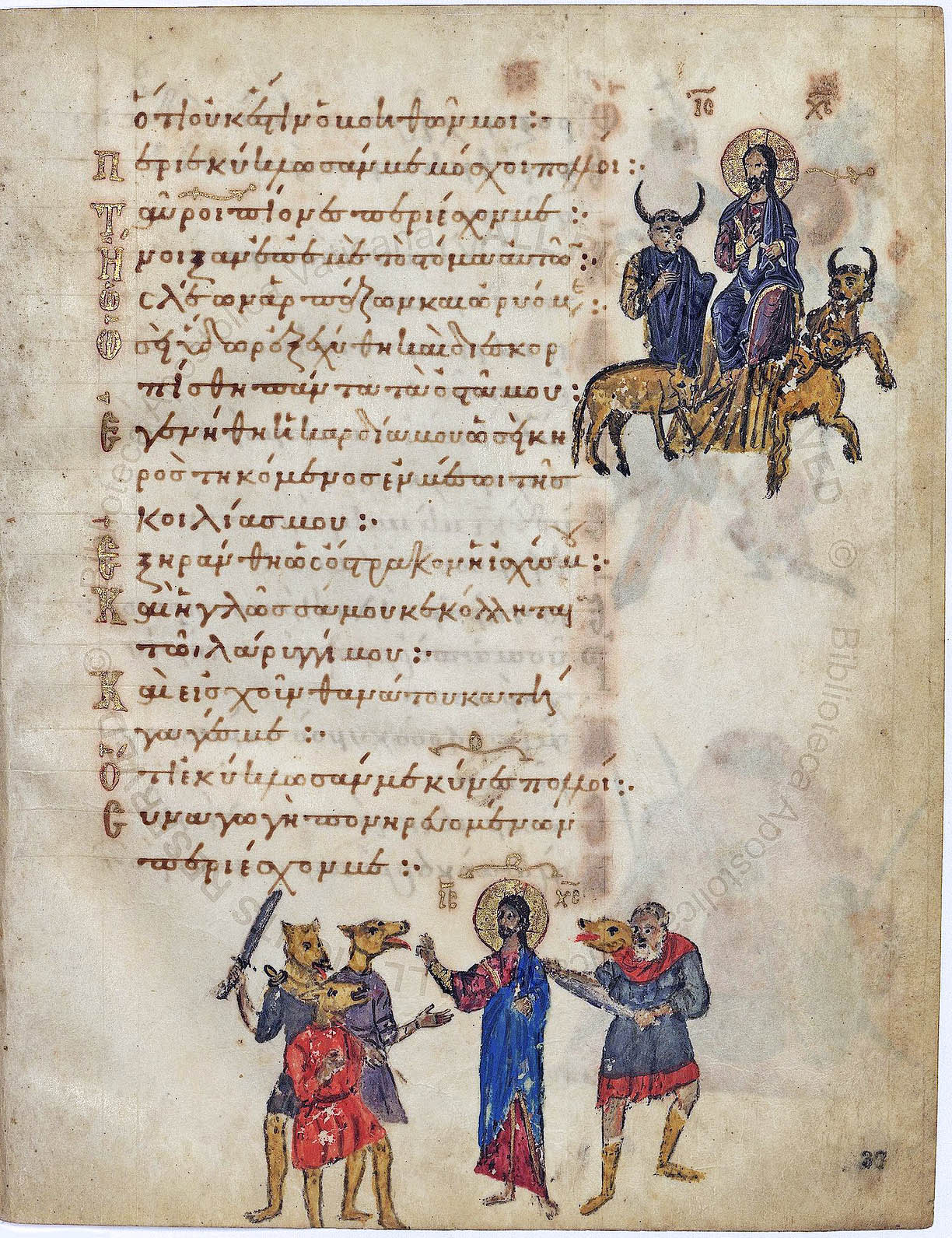

"Yea, dogs are round about me; a company of evildoers encircle me; they have pierced my hands and feet" (Psalm 222:6)

Kiev Psalter (1397).

"Non me Missa iuvat, sed vulpem" ("It's not me this Mass is helping but the fox!") protests the priest whose Mass stipend (a chicken) Reynard has stolen.

See Ysengrimus (ed. Jill Mann), I.751.

Art by Heinrich Leutemann (1824–1905)

Reynard makes his confession.

Art by Christian Votteler (ca. 1895)

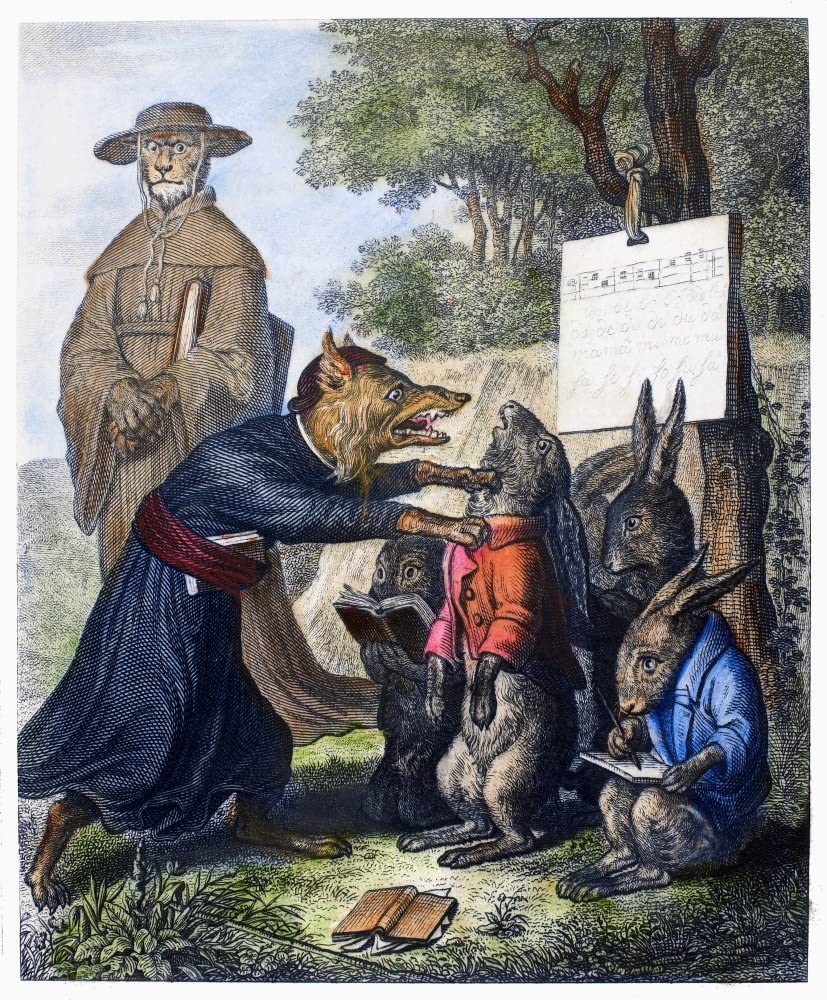

Reynard purports to teach Cuwaert the Creed but cannot restrain himself

Art by Wilhelm Von Kaulbach (1846)

Reynard and Henning

Art by W. French after H. Leutmann (1852).

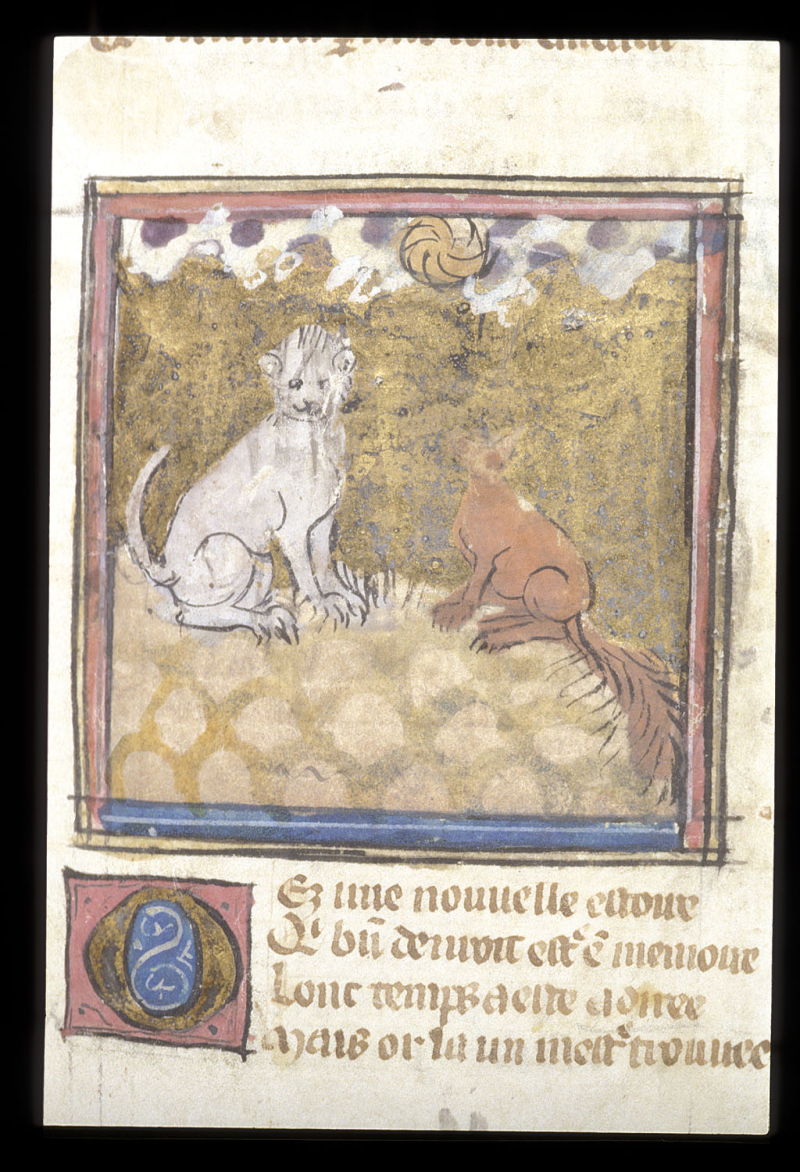

Reynard and Tibert.

From Le Roman de Renart: France or England, 14th century, Add MS 15229, f. 53r

This site explores how Catholic (and more broadly Christian) tradition has engaged the idea of rational animality by way of symbolism, speculation and contrast involving non-human animals. For instance, by discussing:

- beasts and mythical animals as religious symbols

- philosophical/theological contrast between human beings and beasts

- historical speculation about dog-headed men, werewolves, and so forth

- how the tradition has imagined and depicted talking beasts

- how the tradition has imagined and depicted anthropomorphic animals

- the possibility of extraterrestrial life

Contents

- Why are animals worth talking about?

- The term "talking animal"

- The Bible

- Theological considerations

- Historical Catholic speculations about real, non-human intelligent animals

- Talking-animals in lore, amusement, and mockery

- The possibility of extraterrestrial intelligent animals

- The demonic

Why are animals worth talking about?

People might be interested in animals (including real animals, mythical animals, and talking or otherwise anthropomorphized animals) for a variety of reasons, such as:

- appreciation of nature

- aesthetics

- interest in fantasy, science fiction, folklore, or fairy tales

- silliness, amusement, creativity

However, there are also theological and historical reasons to explore the topic of animals from a Catholic perspective, including:

- You are one

- God became an animal and will remain one forever (the Incarnation)

- There are already two animals in heaven (Jesus and Mary)

- Heaven will be filled with animals at the general resurrection

- The Bible uses non-human animal metaphors to communicate truths about God

- Contrasting human beings and beasts or considering other ways God could have formed rational animals helps us to understand possible reasons for why the human body is the way it is (St. Thomas Aquinas, for example, deals with questions like "Why didn't God make human beings with fur?" and "Why did God make human beings to walk on two legs instead of four?" in more than a half-dozen places)

- Sometimes familiar truths become more striking when re-articulated in a new way (For example, the Christian truths communicated by C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia)1

- Historical Catholic culture has fostered its own traditions of talking-animal tales; our Catholic ancestors thought it was worth writing about, depicting, and even dressing up as imaginary or anthropomorphized animals

1. In response to the letter of a woman whose son was troubled because he felt he loved Aslan more than Jesus, C. S. Lewis wrote this reply (Letter to Philinda Krieg of 6/5/1955):

Laurence can't really love Aslan more than Jesus, even if he feels that's what he is doing. For the things he loves Aslan for doing or saying are simply the things Jesus really did and said. So when Laurence thinks he is loving Aslan, he is really loving Jesus: and perhaps loving Him more than he ever did before. Of course there is one thing Aslan has that Jesus has not—I mean, the body of a lion. (But remember, if there are other worlds and they need to be saved and Christ were to save them as He would—He may really have taken all sorts of bodies in them which we don't know about.)

Now if Laurence is bothered because he find the lion-body seems nicer to him than the man-body, I don't think he need be bothered at all. God knows all about the way a little boy's imagination works (He made it, after all) and knows that at a certain age the idea of talking and friendly animals is very attractive. So I don't think He minds if Laurence likes the Lion-body. And anyway, Laurence will find as he grows older, that feeling (liking the lion-body better) will die away of itself, without his taking any trouble about it. So he needn't bother.

The term "talking animal"

The term "talking animal" is really a friendlier / more common way of referring to an intelligent animal, since the ability to speak is a mark of intelligence. Of course, it's possible for an intelligent animal to communicate in a way other than speech (such as by using a signed language or some completely different means). This site doesn't mean to exclude those possibilities by using the term "talking animal."

The main reasons for using the term "talking animal" are:

- It's more common. For example, people are more likely to describe Watership Down as a book about "talking rabbits" than "intelligent rabbits" or "rational rabbits."

The term "talking animal" can be used in several (related) ways:

- All animals (in a philosophical or scientific sense) that have intelligence and thus the ability to speak. In this sense, human beings are the only known talking animals.

- Non-human terrestrial species that are portrayed as having intelligence and thus the ability to speak but not otherwise anthropomorphized. Example: The rabbits in Watership Down.

- Non-human terrestrial species that are portrayed as even further anthropomorphized. Example: Bugs Bunny.

- Any possible intelligent animal, including extraterrestrial species and non-human or semi-human species of myth and fable. Examples: Martians, Werewolves, Centaurs.

Sense #2 seems to be the most normal way people use the term "talking animal." However, this site explores talking/intelligent/rational animals in all four senses.

The Bible

The Bible presents man as distinct from other animals. Genesis emphasizes this by having Adam name the other animals, which indicates both Adam's unique intelligence (he can talk) and his authority/dominion (he can impose names). Similarly, none of the other animals is a fit for Adam, which shows that he is not like them.

In general, when man is expressly said to be "like the beasts," this is something negative, expressing a loss of nobility. For instance: "Man cannot abide in his pomp, he is like the beasts that perish" (Psalm 49:12); " I was stupid and ignorant, I was like a beast toward thee" (Psalm 73:22); "But these, like irrational animals, creatures of instinct, born to be caught and killed, reviling in matters of which they are ignorant, will be destroyed in the same destruction with them" (2 Peter 2:12).

At the same time, the Bible employs many positive metaphors involving specific beasts. Sometimes a beast image is used for both God and man, sometimes just for man, sometimes just for God, and sometimes for Christ, who is God and man. Catholic tradition has developed further animal symbolism, sometimes building on Scripture, though not always. For instance, the unicorn, the pelican, and the gryphon have all been used as symbols of Christ in Christian tradition.

Beast images for both God and man

"For he will deliver you from the snare of the fowler and from the deadly pestilence; he will cover you with his pinions, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness is a shield and buckler." (Psalm 91:3–4) [God is imagined as a mother bird shielding her chicks from fowlers with her wings.]

Beast images for man in relation to God

Perhaps the best-known beast image for man in relation to God is that of the sheep. "The LORD is my shepherd, I shall not want; he makes me lie down in green pastures. He leads me beside still waters." (Psalm 22:1–2) A similar metaphor is found in Luke 15:1–7 (Matthew 18:12–14) with the Parable of the Lost Sheep. Likewise, Christ refers to himself as a shepherd and his followers as sheep in John 10. See also Matthew 10:16; 25:32; 26:31; and John 21:15–17. Cf. Ezekiel 34.

The image of fishing and of humanity as fish appear in the Gospels as well. See Mark 1:7; Matthew 4:19; 13:47.

Likewise, Christ contrasts positive and negative beast imagery to differentiate his followers and those resistant to his teaching. "Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves; so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves." (Matthew 10:16) Compare this to the contrast between the sheep and the goats at the final judgment in Matthew 25:32.

Christ's references to dogs are interesting. There is the general advice: "Do not give dogs what is holy; and do not throw your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under foot and turn to attack you" (Matthew 7:6). However, the Lord also uses dog imagery for non-Israelites, though in a case where he ultimately affirms the faith and inclusion of the woman in question (Matthew 15:21–28; cf. Mark 7:24–30):

And Jesus went away from there and withdrew to the district of Tyre and Sidon. And behold, a Canaanite woman from that region came out and cried, "Have mercy on me, O Lord, Son of David; my daughter is severely possessed by a demon." But he did not answer her a word. And his disciples came and begged him, saying, "Send her away, for she is crying after us." He answered, "I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel." But she came and knelt before him, saying, "Lord, help me." And he answered, "It is not fair to take the children's bread and throw it to the dogs." She said, "Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table." Then Jesus answered her, "O woman, great is your faith! Be it done for you as you desire." And her daughter was healed instantly.

Beast images for God

"How precious is thy steadfast love, O God! The children of men take refuge in the shadow of thy wings." (Psalm 36:7)

"Be merdiful to me, O God, be merciful to me, for in thee my soul takes refuge; in the shadow of thy wings I will take refuge, till the storms of destruction pass by." (Psalm 57:1)

"Let me dwell in thy tent for ever! Oh to be safe under the shelter of thy wings!" (Psalm 61:4)

"for thou hast been my help, and in the shadow of thy wings I sing for joy." (Psalm 63:4)

A particularly important instance of a beast-image for God is the Holy Spirit's appearance at Christ's Baptism in the likeness of a dove. In Summa theologiae III, q. 39, aa. 6-7, St. Thomas Aquinas argues that this was a real, living dove that popped into existence for the purpose and then popped out of existence after the appearance. At the same time, the dove was not assumed by the Holy Spirit into a hypostatic union. In other words, the dove signified the Holy Spirit and was thus part of a visible divine mission of the Holy Spirit (cf. Summa theologiae I, q. 43, a. 7), but the Holy Spirit was not a dove in the way that God the Son is a man.

Beast images for Christ, the God-man

"O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not!" (Matthew 23:37) [Christ is imagined as a mother bird shielding her chicks.]

|

The Lamb  The Ghent altarpiece |

In addition to using titles like "Lamb of God" for Jesus (John 1:29; cf. 19:36), God communicates this truth to St. John in a mystical experience: "And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders, I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth" (Rev 5:6). In other words, God depicts Jesus visibly as a lamb in order to reveal a truth about him, namely, that he is the acceptable sacrificial victim whose blood saves his people from their sins. The depiction of Jesus as a lamb and references to him as a lamb pervade Catholic tradition. For instance, the Easter sequence proclaims: Agnus redemit oves ("The Lamb has redeemed the sheep!"), and Jesus in the Eucharist is directly addressed as "Lamb of God" at every Mass. |

|

The Lion  Rochester Bestiary, The British Library, Ms. Royal 12 F XIII, fol. 5. |

"Weep not; lo, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals." (Revelation 5:5) |

|

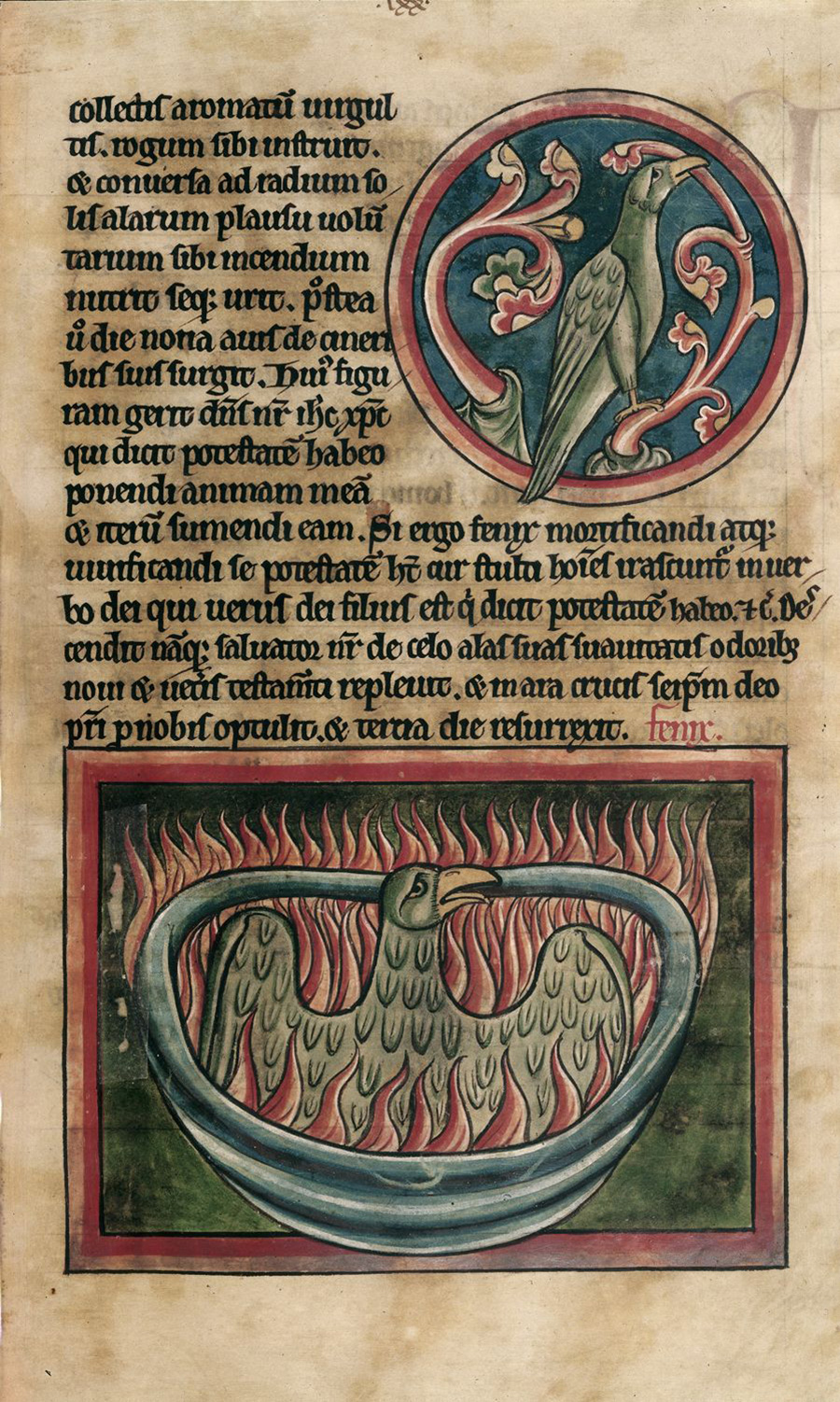

The Unicorn  The Morgan Library, MS M.1201 |

Medieval bestiaries, following a relatively ancient tradition, usually identify the unicorn as a symbol of Christ for a variety of reasons, including Scriptural references to the "horn" of the Messiah (1 Sm 2:10), the blessing of Joseph in Deuteronomy 33:17, the fact that the unicorn is a symbol of the Jewish people (the horn standing for worship of the one God), and the unicorn-hunt allegory for the Incarnation. |

|

The Pelican  Oratorio of St. John the Baptist, Urbino, Italy |

Legend holds that the pelican feeds its young by piercing its breast and giving them its own blood. Thus it is an allegory for Christ, who feeds the faithful with the Eucharist. Thus, St. Thomas Aquinas's Eucharistic hymn, Adoro te devote invokes Christ as Pie pellicane, Iesu Domine ("O pious pellican, Lord Jesus"). |

|

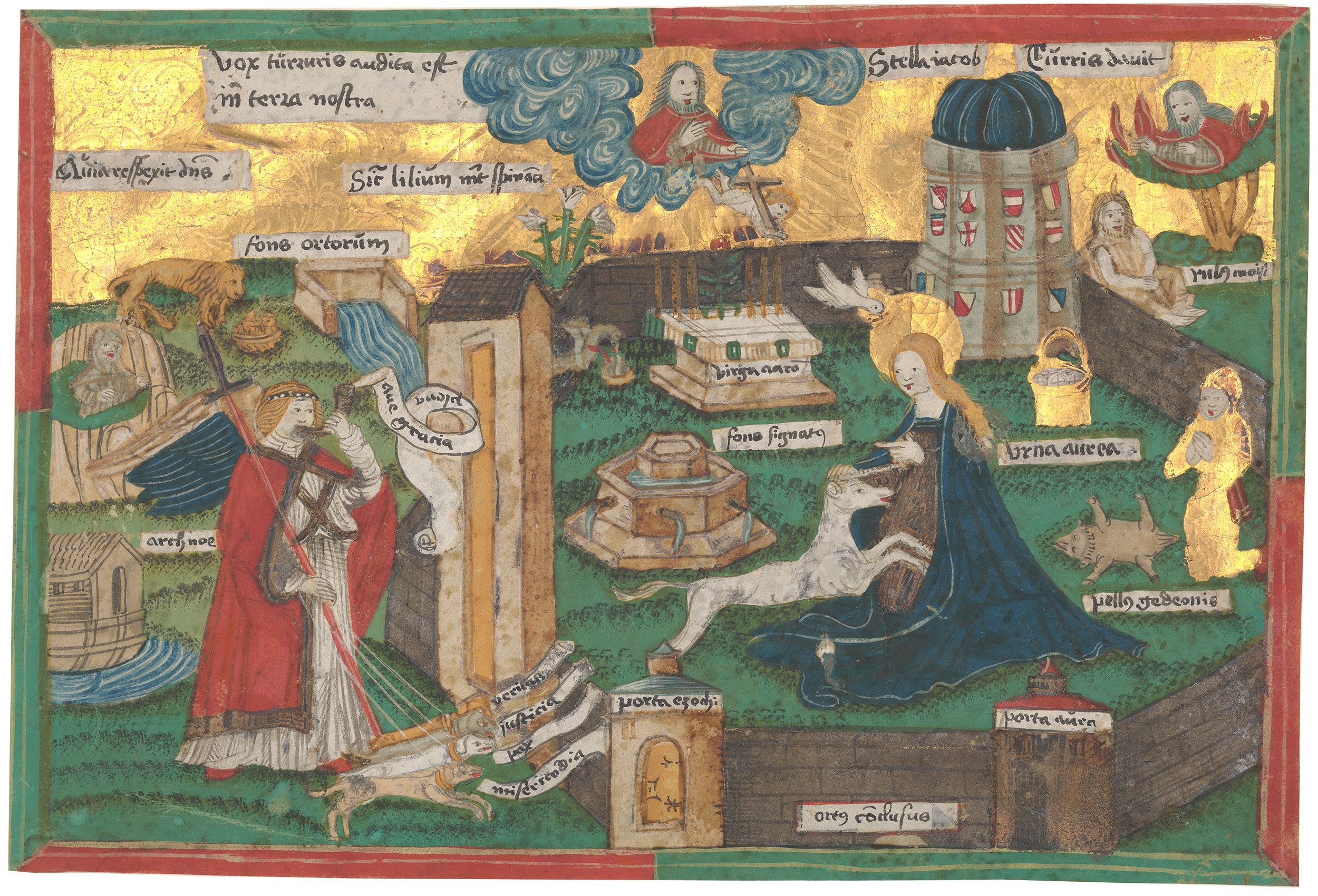

The Phoenix  The British Library, Harley Ms. 4751, fol. 45. |

The phoenix is a symbol of Christ in his dying and rising from the dead. It also symbolizes the paschal mystery and the resurrection generally. |

|

The Gryphon  British Library, Harley MS 3244, folio 38v. |

Although it also symbolizes other things, at times the gryphon has been taken as a symbol for Christ because of its "two natures" (lion and eagle), representing the humanity and divinity of Christ. The lion is the king the earthly realm, the eagle the king of heaven. |

The Tetramorph and the Four Evangelists

Ezekiel 1:5–11:

And from the midst of it came the likeness of four living creatures. And this was their appearance: they had the form of men, but each had four faces, and each of them had four wings. Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the sole of a calf's foot; and they sparkled like burnished bronze. Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. And the four had their faces and their wings thus: their wings touched one another; they went every one straight forward, without turning as they went. As for the likeness of their faces, each had the face of a man in front; the four had the face of a lion on the right side, the four had the face of an ox on the left side, and the four had the face of an eagle at the back. Such were their faces. And their wings were spread out above; each creature had two wings, each of which touched the wing of another, while two covered their bodies.

Revelation 4:6–9:

And round the throne, on each side of the throne, are four living creatures, full of eyes in front and behind: the first living creature like a lion, the second living creature like an ox, the third living creature with the face of a man, and the fourth living creature like a flying eagle. And the four living creatures, each of them with six wings, are full of eyes all round and within, and day and night they never cease to sing, "Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come!" And whenever the living creatures give glory and honor and thanks to him who is seated on the throne, who lives for ever and ever,

From an early time, the four animals of Ezekiel and Revelation have been seen as a symbol of the four Gospel writers. St. Irenaeus of Lyon (ca. 130–202) writes in Adversus haereses III, chap. 11, no. 8 [Translated by Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885), revised by Kevin Knight.]:

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is scattered throughout all the world, and the "pillar and ground" 1 Timothy 3:15 of the Church is the Gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars, breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh. From which fact, it is evident that the Word, the Artificer of all, He that sits upon the cherubim, and contains all things, He who was manifested to men, has given us the Gospel under four aspects, but bound together by one Spirit. As also David says, when entreating His manifestation, "You that sits between the cherubim, shine forth." For the cherubim, too, were four-faced, and their faces were images of the dispensation of the Son of God. For, [as the Scripture] says, "The first living creature was like a lion," Revelation 4:7 symbolizing His effectual working, His leadership, and royal power; the second [living creature] was like a calf, signifying [His] sacrificial and sacerdotal order; but "the third had, as it were, the face as of a man,"— an evident description of His advent as a human being; "the fourth was like a flying eagle," pointing out the gift of the Spirit hovering with His wings over the Church. And therefore the Gospels are in accord with these things, among which Christ Jesus is seated. For that according to John relates His original, effectual, and glorious generation from the Father, thus declaring, "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." John 1:1 Also, "all things were made by Him, and without Him was nothing made." For this reason, too, is that Gospel full of all confidence, for such is His person. But that according to Luke, taking up [His] priestly character, commenced with Zacharias the priest offering sacrifice to God. For now was made ready the fatted calf, about to be immolated for the finding again of the younger son. Matthew, again, relates His generation as a man, saying, "The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham;" and also, "The birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise." This, then, is the Gospel of His humanity; for which reason it is, too, that [the character of] a humble and meek man is kept up through the whole Gospel. Mark, on the other hand, commences with [a reference to] the prophetical spirit coming down from on high to men, saying, "The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, as it is written in Esaias the prophet,"— pointing to the winged aspect of the Gospel; and on this account he made a compendious and cursory narrative, for such is the prophetical character. And the Word of God Himself used to converse with the ante-Mosaic patriarchs, in accordance with His divinity and glory; but for those under the law he instituted a sacerdotal and liturgical service. Afterwards, being made man for us, He sent the gift of the celestial Spirit over all the earth, protecting us with His wings. Such, then, as was the course followed by the Son of God, so was also the form of the living creatures; and such as was the form of the living creatures, so was also the character of the Gospel. For the living creatures are quadriform, and the Gospel is quadriform, as is also the course followed by the Lord. For this reason were four principal (καθολικαί) covenants given to the human race: one, prior to the deluge, under Adam; the second, that after the deluge, under Noah; the third, the giving of the law, under Moses; the fourth, that which renovates man, and sums up all things in itself by means of the Gospel, raising and bearing men upon its wings into the heavenly kingdom.

Balaam's Ass

The most famous incident in the Bible where God communicates an important message through a talking beast is Balaam's Ass (Numbers 22-24).

Numbers 22:21–35:

And God came to Balaam at night and said to him, "If the men have come to call you, rise, go with them; but only what I bid you, that shall you do." So Balaam rose in the morning, and saddled his ass, and went with the princes of Moab. But God's anger was kindled because he went; and the angel of the LORD took his stand in the way as his adversary. Now he was riding on the ass, and his two servants were with him. And the ass saw the angel of the LORD standing in the road, with a drawn sword in his hand; and the ass turned aside out of the road, and went into the field; and Balaam struck the ass, to turn her into the road. Then the angel of the LORD stood in a narrow path between the vineyards, with a wall on either side. And when the ass saw the angel of the LORD, she pushed against the wall, and pressed Balaam's foot against the wall; so he struck her again. Then the angel of the LORD went ahead, and stood in a narrow place, where there was no way to turn either to the right or to the left. When the ass saw the angel of the LORD, she lay down under Balaam; and Balaam's anger was kindled, and he struck the ass with his staff. Then the LORD opened the mouth of the ass, and she said to Balaam, "What have I done to you, that you have struck me these three times?" And Balaam said to the ass, "Because you have made sport of me. I wish I had a sword in my hand, for then I would kill you." And the ass said to Balaam, "Am I not your ass, upon which you have ridden all your life long to this day? Was I ever accustomed to do so to you?" And he said, "No." Then the LORD opened the eyes of Balaam, and he saw the angel of the LORD standing in the way, with his drawn sword in his hand; and he bowed his head, and fell on his face. And the angel of the LORD said to him, "Why have you struck your ass these three times? Behold, I have come forth to withstand you, because your way is perverse before me; and the ass saw me, and turned aside before me these three times. If she had not turned aside from me, surely just now I would have slain you and let her live." Then Balaam said to the angel of the LORD, "I have sinned, for I did not know that thou didst stand in the road against me. Now therefore, if it is evil in thy sight, I will go back again." And the angel of the LORD said to Balaam, "Go with the men; but only the word which I bid you, that shall you speak." So Balaam went on with the princes of Balak.

In De Genesi ad litteram XI, 29.37, St. Augustine explains Balaam's Ass in the same way that he explains the talking serpent in Genesis 3, saying that it is an angel that spoke through the donkey just as it was a demon that spoke through the serpent:

And thus I have thought [the opinion that it was the devil who spoke through the serpent] is the one to recommend, lest anyone who thinks that animals lacking reason can possess human understanding or can be changed all of a sudden into a rational animal, be seduced to that ridiculous and harmful opinion that there is a rotation of souls, whether of men into beasts or of beasts into men. And so, therefore, the serpent spoke to man in the way the donkey on which Balaam was sitting spoke to man, except that the former was the work of a demon and the latter the work of an angel.

Nebuchadnezzar's Transformation

(Dan 4:31–34a):

While the words were still in the king's mouth, there fell a voice from heaven, "O King Nebuchadnez'zar, to you it is spoken: The kingdom has departed from you, and you shall be driven from among men, and your dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field; and you shall be made to eat grass like an ox; and seven times shall pass over you, until you have learned that the Most High rules the kingdom of men and gives it to whom he will." Immediately the word was fulfilled upon Nebuchadnez'zar. He was driven from among men, and ate grass like an ox, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven till his hair grew as long as eagles' feathers, and his nails were like birds' claws. At the end of the days I, Nebuchadnez'zar, lifted my eyes to heaven, and my reason returned to me, and I blessed the Most High, and praised and honored him who lives for ever.

Theological considerations

To introduce the theological perspective, we have no better guide than St. Thomas Aquinas, OP (1225–74). All quotations from the Summa theologiae are from The Summa Theologiae of St. Thomas Aquinas, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, 2nd rev. ed. (1920), unless otherwise noted.

Why is man's body the way it is?

|

From the appendix of Niccolò Perotti (1429–80) to the fables of the Phaedrus (Appendix Perottina), no. 3 (Loeb Classical Library, Greek series, 436:372, 374):

Arbitrio si natura finxisset meo |

Translation by Ben Edwin Perry (Loeb Classical Library, Greek series, 436:373, 375):

If Nature had fashioned the human species according to my ideas it would have been far better equipped. She would have bestowed upon us all the advantages that indulgent Fortune has given singly to the various animals; the strength of the elephant, the onrushing force of the lion, the longevity of the crow, the vaunting pride of the fierce bull, the peaceful docility of the swift horse; and at the same time man would have, in addition, his own ingenuity. No doubt Jupiter in the heavens is laughing to himself, since it was he who denied all this to men with profound foresight, lest our audacity should seize the sceptre of the world. |

In Summa theologiae I, q. 91, a. 3, St. Thomas compares and contrasts man's body with the bodies of other animals. He doesn't shy away from issues like "Why don't human beings have fur?" and "Why do they walk on two legs?" and "Why don't they have paws or talons?"

It is worth quoting the entire article:

Objection 1. It would seem that the body of man was not given an apt disposition. For since man is the noblest of animals, his body ought to be the best disposed in what is proper to an animal, that is, in sense and movement. But some animals have sharper senses and quicker movement than man; thus dogs have a keener smell, and birds a swifter flight. Therefore man's body was not aptly disposed.

Objection 2. Further, perfect is what lacks nothing. But the human body lacks more than the body of other animals, for these are provided with covering and natural arms of defense, in which man is lacking. Therefore the human body is very imperfectly disposed.

Objection 3. Further, man is more distant from plants than he is from the brutes. But plants are erect in stature, while brutes are prone in stature. Therefore man should not be of erect stature.

On the contrary, It is written (Ecclesiastes 7:30): "God made man right."

I answer that, All natural things were produced by the Divine art, and so may be called God's works of art. Now every artist intends to give to his work the best disposition; not absolutely the best, but the best as regards the proposed end; and even if this entails some defect, the artist cares not: thus, for instance, when man makes himself a saw for the purpose of cutting, he makes it of iron, which is suitable for the object in view; and he does not prefer to make it of glass, though this be a more beautiful material, because this very beauty would be an obstacle to the end he has in view. Therefore God gave to each natural being the best disposition; not absolutely so, but in the view of its proper end. This is what the Philosopher says (Phys. ii, 7): "And because it is better so, not absolutely, but for each one's substance."

Now the proximate end of the human body is the rational soul and its operations; since matter is for the sake of the form, and instruments are for the action of the agent. I say, therefore, that God fashioned the human body in that disposition which was best, as most suited to such a form and to such operations. If defect exists in the disposition of the human body, it is well to observe that such defect arises as a necessary result of the matter, from the conditions required in the body, in order to make it suitably proportioned to the soul and its operations.

Reply to Objection 1. The sense of touch, which is the foundation of the other senses, is more perfect in man than in any other animal; and for this reason man must have the most equable temperament of all animals. Moreover man excels all other animals in the interior sensitive powers, as is clear from what we have said above (I:78:4). But by a kind of necessity, man falls short of the other animals in some of the exterior senses; thus of all animals he has the least sense of smell. For man needs the largest brain as compared to the body; both for his greater freedom of action in the interior powers required for the intellectual operations, as we have seen above (I:84:7); and in order that the low temperature of the brain may modify the heat of the heart, which has to be considerable in man for him to be able to stand erect. So that size of the brain, by reason of its humidity, is an impediment to the smell, which requires dryness. In the same way, we may suggest a reason why some animals have a keener sight, and a more acute hearing than man; namely, on account of a hindrance to his senses arising necessarily from the perfect equability of his temperament. The same reason suffices to explain why some animals are more rapid in movement than man, since this excellence of speed is inconsistent with the equability of the human temperament.

Reply to Objection 2. Horns and claws, which are the weapons of some animals, and toughness of hide and quantity of hair or feathers, which are the clothing of animals, are signs of an abundance of the earthly element; which does not agree with the equability and softness of the human temperament. Therefore such things do not suit the nature of man. Instead of these, he has reason and hands whereby he can make himself arms and clothes, and other necessaries of life, of infinite variety. Wherefore the hand is called by Aristotle (De Anima iii, 8), "the organ of organs." Moreover this was more becoming to the rational nature, which is capable of conceiving an infinite number of things, so as to make for itself an infinite number of instruments.

Reply to Objection 3. An upright stature was becoming to man for four reasons.

First, because the senses are given to man, not only for the purpose of procuring the necessaries of life, which they are bestowed on other animals, but also for the purpose of knowledge. Hence, whereas the other animals take delight in the objects of the senses only as ordered to food and sex, man alone takes pleasure in the beauty of sensible objects for its own sake. Therefore, as the senses are situated chiefly in the face, other animals have the face turned to the ground, as it were for the purpose of seeking food and procuring a livelihood; whereas man has his face erect, in order that by the senses, and chiefly by sight, which is more subtle and penetrates further into the differences of things, he may freely survey the sensible objects around him, both heavenly and earthly, so as to gather intelligible truth from all things.

Secondly, for the greater freedom of the acts of the interior powers; the brain, wherein these actions are, in a way, performed, not being low down, but lifted up above other parts of the body.

Thirdly, because if man's stature were prone to the ground he would need to use his hands as fore-feet; and thus their utility for other purposes would cease.

Fourthly, because if man's stature were prone to the ground, and he used his hands as fore-feet, he would be obliged to take hold of his food with his mouth. Thus he would have a protruding mouth, with thick and hard lips, and also a hard tongue, so as to keep it from being hurt by exterior things; as we see in other animals. Moreover, such an attitude would quite hinder speech, which is reason's proper operation.

Nevertheless, though of erect stature, man is far above plants. For man's superior part, his head, is turned towards the superior part of the world, and his inferior part is turned towards the inferior world; and therefore he is perfectly disposed as to the general situation of his body. Plants have the superior part turned towards the lower world, since their roots correspond to the mouth; and their inferior part towards the upper world. But brute animals have a middle disposition, for the superior part of the animal is that by which it takes food, and the inferior part that by which it rids itself of the surplus.

Reason and Hands

Following Aristotle, St. Thomas observes that in place of the endowments given to other animals, human beings have the special gifts of reason and hands, which allow them to make for themselves what they need to survive and flourish rather than relying on what is built into their bodies.

Super III Sent., d. 33, q. 1, a. 2, qc. 1, arg. 3 / ad 3 [my translation]:

Objection 3: Man is the most perfect among the other animals. But there is in other animals a disposition to do what befits them, as there is for the swallow to make a nest. Since, then, the virtues are nothing other than inclinations toward works that are fitting to man, it seems that the natural virtues are implanted in man.

[...]

Reply to Objection 3: Because man has reason, which is collative, he is in relation to many actions, of which reason is the principle. And thus what is necessary for covering and defense has not been provided man by nature, as it has for other animals, such as fur and claws. For a determinate instrument could not be fit for such variable and different actions. And thus hands are given him, whereby he can make for himself what is necessary as befits him from reason. And likewise, there could not be in man a fulfilment from nature, since there is not something identical that is fitting for everyone. For the mean of virtue must be understood in different cases in different ways.

In that quotation, St. Thomas points to reason as the principle of human actions. Because reason can deal with universal in various combinations, it makes man open to a wide range of actions. Thus, just as man's body doesn't have narrowly determined features (like claws) that would have only a small number of uses but instead hands that he can use to interact with the world and make tools to accomplish many varied tasks, so also he does not have the natural virtues in a built-in way but instead has to develop them by reasoned activity.

Cf. De veritate, q. 22, a. 7, co. [translated by Robert W. Schmidt, S.J. (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1954)]:

There is a difference in the way in which providence is exercised in regard to man and in regard to the other animals both as to his body and as to his soul. For other animals are provided with special coverings for their bodies, such as a tough hide, feathers, and the like, and also special weapons, such as horns, claws, and so forth. This is because they have just a few ways of acting to which they can adapt definite instruments. But man is provided with those things in a general way inasmuch as there has been given to him by nature hands by which he is able to prepare for himself a variety of coverings and protections. This is because man’s reason is so manifold and extends to so many different things that definite tools sufficient for him could not be provided for him ahead of time.

Cf. Contra impugnantes II, chap. 4, ad 1 [my translation]:

That human nature itself inclines to working with the hands is indicated by the body's arrangement. For nature did not give man clothing, like it gave fur to animals, nor weapons, like it gave horns to cattle and claws to lions, nor has nature prepared any food for man except milk, as Avicenna says. But in place of all these, it gave him reason, whereby he can provide all these things for himself and hands with which he could put into practice the provision of reason, as the Philosopher says in De animalibus 14.

Cf. Summa theologiae I, q. 76, a. 5, arg. 4 / ad 4:

Objection 4: What is susceptible of a more perfect form should itself be more perfect. But the intellectual soul is the most perfect of souls. Therefore since the bodies of other animals are naturally provided with a covering, for instance, with hair instead of clothes, and hoofs instead of shoes; and are, moreover, naturally provided with arms, as claws, teeth, and horns; it seems that the intellectual soul should not have been united to a body which is imperfect as being deprived of the above means of protection.

[...]

Reply to Objection 4: The intellectual soul as comprehending universals, has a power extending to the infinite; therefore it cannot be limited by nature to certain fixed natural notions, or even to certain fixed means whether of defence or of clothing, as is the case with other animals, the souls of which are endowed with knowledge and power in regard to fixed particular things. Instead of all these, man has by nature his reason and his hands, which are "the organs of organs" (De Anima iii), since by their means man can make for himself instruments of an infinite variety, and for any number of purposes.

Applying St. Thomas's principles, we can say that God has provided human beings with reason and with a body fitted for the internal senses (such as imagination) necessary to aid in the reasoning process, since humans make use phantasms even when engaging in abstract thought. So the human body is formed to aid in what is properly human, i.e., reasoning. Further, in order to put into practice the fruits of human intelligence and creativity, God has given human beings hands, which they can use to make almost anything. Unlike hooves or claws that might be limited to a small number of uses, hands can be used to fashion a more universal range of objects, which is in keeping with the universal scope of human reason. In short, God has provided man with what he needs to consider the universal and to exercise his own creativity through cultivating and modifying the physical world around him, for which hands are most suitable.

St. Thomas extends this line of reasoning to shoes and clothing. In other words, God has not given human beings fur, feather, or scales, but he has given them the means whereby they can make for themselves what they need for bodily protection. A further use of clothing is adornment, the value of which St. Thomas recognizes (e.g., Summa theologiae I, q. 70, a. 1; I-II, q. 102, a. 4). Thus the creation of elaborate vestments for divine worship, elegant clothing for important occasions, and even a variety of costuming for fun and entertainment can be appropriate exercises of man's rational animality. Rather than giving man fur, feathers, or scales, God has given man the ability to dress in a great variety of ways through his own freedom and artistry.

St. Thomas further observes that human beings cannot practically live out this vision in isolation. Not everyone can do everything. Thus, in society people cooperate to accomplish the goals mentioned above. So, for instance, someone might make liturgical vestments or costumes to be used by others. Thus, he explains in De regno I, cap. 1 co. [translated by Gerald B. Phelan, revised by I. Th. Eschmann, O.P. and Joseph Kenny, O.P. (Toronto: The Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1949)]:

For all other animals, nature has prepared food, hair as a covering, teeth, horns, claws as means of defence or at least speed in flight, while man alone was made without any natural provisions for these things. Instead of all these, man was endowed with reason, by the use of which he could procure all these things for himself by the work of his hands. Now, one man alone is not able to procure them all for himself, for one man could not sufficiently provide for life, unassisted. It is therefore natural that man should live in the society of many.

Moreover, all other animals are able to, discern, by inborn skill, what is useful and what is injurious, even as the sheep naturally regards the wolf as his enemy. Some animals also recognize by natural skill certain medicinal herbs and other things necessary for their life. Man, on the contrary, has a natural knowledge of the things which are essential for his. life only in a general fashion, inasmuch as he is able to attain knowledge of the particular things necessary for human life by reasoning from natural principles. But it is not possible for one man to arrive at a knowledge of all these things by his own individual reason. It is therefore necessary for man to live in a multitude so that each one may assist his fellows, and different men may be occupied in seeking, by their reason, to make different discoveries—one, for example, in medicine, one in this and another in that.

This point is further and most plainly evidenced by the fact that the. use of speech is a prerogative proper to man. By this means, one man is able fully to express his conceptions to others. Other animals, it is true, express their feelings to one another in a general way, as a dog may express anger by barking and other animals give vent to other feelings in various fashions. But man communicates with his kind more completely than any other animal known to be gregarious, such as the crane, the ant or the bee.—With this in mind, Solomon says: “It is better that there be two than one; for they have the advantage of their company.”

Besides providing bodily protection, clothing serves social purposes. Liturgical vestments help distinguish worship from ordinary activity and elevate the mind and heart to God. Uniforms make people's roles in society clearer to others. Mascot costumes foster community and a sense of identity and pride at sporting events. Of course, like anything otherwise good or legitimate, clothing can be abused (Summa theologiae II-II, q. 169, aa. 1–2). For instance, some use clothing that is too costly or otherwise inappropriate to the situation. Others seek undeserved honor by wearing certain clothing. Others might dress immodestly or in a way that harms their neighbor. However, the use of clothing to highlight the dignity of one's office (vestments, royal robes, academic regalia, etc.) remains legitimate in itself (Contra impugnantes II, chap. 1, ad 1).

Why does man not have a tail?

St. Albert the Great, following Aristotle, offers the following explanation for why man does not have a tail (De animalibus XIV, tract.2, cap.4 [ed. Stadler, pp. 972–73, my translation]):

Now as for the member on the backsides of animals near the hips and legs (called the "tail"), as regards the way man is built there is a contrast between man and the creation of other, four-footed animals. For all four-footed animals have a large or small tail, not only those animals that bear live young but also four-footed animals that lay eggs have a large or small tail. And some tails also have fur while others do not. Man, however, does not have a tail at all, just as no four-footed animal has huanches.

Now the reason for man not to have a tail is that the tail is principally to cover the anus so that it does not get cold. But man has very fleshy hips that sufficiently cover the anus and this same fleshiness takes to itself the substance of the tail. Further, since man has an upright body, the tail would get in the way of his movement and his lying-down and sitting. And thus it is quite well that man is deprived of a tail. Other animals, however, are deprived of flesh in the buttocks so that they do not have as much flesh in them as man does proportionately. For although animals that bear live young have hips and legs and their creation is from bones and nerves and they might even have a lot of flesh in them, as in the case of fat horses, because they do not have upright bodies, the anus is not covered for them by the hips and buttocks. Hence among all these there is almost a single reason, which is that man alone among the animals has an upright body, as we have said. Therefore in order for there to be a regular slope to the body and a regular pathway to the lower part on account of lightness and flatness, nature has taken the flesh from the parts of the body that hang down and added it to the buttocks and made the muscles there larger than they are in another part of the body. And for this reason man's haunches are very fleshy and as is that which is near the hips and the inside of the leg, both above and below the knee.

Now nature saw to it this way so that there would not be too much bodyweight on top of thin legs and so that man's upright body would proportionately taper off, since it is then easier to carry and is more appropriate for his actions. But the hips and legs of four-footed animals are strong due to nerve and bone in order to carry the bodyweight. And the four feet are like four supports in front and back, for which reason, too, a four-footed animal is born standing up without effort, whereas man cannot stand upright for a long period of time but needs rest, both because of the delicacy of his component parts and because his whole body is balanced on only two supports. The hips, therefore, as is clear from what has been said, and the inside of the legs in man are very fleshy for the stated reason. And thus he does not have a tail because all the food goes to providing nourishment for the hips and legs. And because he has fleshy haunches he lacks a tail, which he would necessarily need if not for the aforementioned. Now a four-footed animal and the other kinds are the reverse, since the majority of their flesh and weight is in the front part. For this reason they do not have very fleshy haunches and legs in respect to their body, nor are their legs very meaty and tough in the muscles of the buttocks and in the calves below the hough. Thus in order for the member of the anus (from which excess passes) and likewise the genitals (which need great protection from cold and from what could harm them) to be protected by something else, nature made them a tail. But the ape does not have haunches due to the fact that its form is a composite of the form of man and of a four-footed animal, and its backside is more like a four-footed animal.

Moreover, there are many differences among tails, which nature does not use only for one function (protecting the anus), but for many auxiliary functions as well.

It is evident that Albert, as expected, has appropriated Aristotle's explanation. In On the Parts of Animals IV, 689b1–690a4 [translated by William Ogle], Aristotle writes:

The posterior portion of the body and the parts about the legs are peculiar in man as compared with quadrupeds. Nearly all these latter have a tail, and this whether they are viviparous or oviparous. For, even if the tail be of no great size, yet they have a kind of scut, as at any rate a small representative of it. But man is tail-less. He has, however, buttocks, which exist in none of the quadrupeds. His legs also are fleshy (as too are his thighs and feet); while the legs in all other animals that have any, whether viviparous or not, are fleshless, being made of sinew and bone and spinous substance. For all these differences there is, so to say, one common explanation, and this is that of all animals man alone stands erect. It was to facilitate the maintenance of this position that Nature made his upper parts light, taking away some of their corporeal substance, and using it to increase the weight of lithe parts below, so that the buttocks, the thighs, and the calves of the legs were all made fleshy. The character which she thus gave to the buttocks renders them at the same time useful in resting the body. For standing causes no fatigue to quadrupeds, and even the long continuance of this posture produces in them no weariness; for they are supported the whole time by four props, which is much as though they were lying down. But to man it is no task to remain for any length of time on his feet, his body demanding rest in a sitting position. This, then, is the reason why man has buttocks and fleshy legs; and the presence of these fleshy parts explains why he has no tail. For the nutriment which would otherwise go to the tail is used up in the production of these parts, while at the same time the existence of buttocks does away with the necessity of a tail. But in quadrupeds and other animals the reverse obtains. For they are of dwarf-like form, so that all the pressure of their weight and corporeal substance is on their upper part, and is withdrawn from the parts below. On this account they are without buttocks and have hard legs. In order, however, to cover and protect that part which serves for the evacuation of excrement, nature has given them a tail of some kind or other, subtracting for the purpose some of the nutriment which would otherwise go to the legs. Intermediate in shape between man and quadrupeds is the ape, belonging therefore to neither or to both, and having on this account neither tail nor buttocks; no tail in its character of biped, no buttocks in its character of quadruped. There is great diversity of so-called tails; and this organ like others is sometimes used by nature for by-purposes, being made to serve not only as a covering and protection to the fundament, but also for other uses and advantages of its possessor.

Honoring the particularities of human animality

Catholic tradition is replete with examples of reverential acts rooted in the precise determinations of human animality. Events such as the conception of Christ and Mary, as well as their births, the Lord's circumsision, the transfiguration, and even the institution of the Eucharist all depend on the specific ways in which the human body is shaped, its organs, and how it functions. If rational animality were expressed differently (for instance, if humans laid eggs instead of bearing live young, or consumed nourishment in a way other than eating), the Incarnation itself would look different and different liturgical celebrations would result.

The Catholic tradition, following Scripture, also gives honor to particular organs of the human body: "Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!" (Luke 1:42); "Blessed is the womb that bore you, and the breasts at which you nursed!" (Lk 11:27). Other examples include the honor given to the heart of Jesus and the heart of Mary.

For instance, commenting on the Passion of Christ, St. Thomas highlights the signficance of the Lord's suffering in terms of the particularities of the human body (ST III, q. 46, a. 5, ad 3):

Thirdly, it may be considered with regard to His bodily members. In His head He suffered from the crown of piercing thorns; in His hands and feet, from the fastening of the nails; on His face from the blows and spittle; and from the lashes over His entire body. Moreover, He suffered in all His bodily senses: in touch, by being scourged and nailed; in taste, by being given vinegar and gall to drink; in smell, by being fastened to the gibbet in a place reeking with the stench of corpses, "which is called Calvary"; in hearing, by being tormented with the cries of blasphemers and scorners; in sight, by beholding the tears of His Mother and of the disciple whom He loved.

Man's animality does not detract from his proper dignity, though irrationality does

The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) speaks of man as belonging both to the spiritual and material realms. Man is thus similar to the angels in some respects and similar to the beasts in some respects [From H. J. Schroeder, Disciplinary Decrees of the General Councils: Text, Translation and Commentary (St. Louis: B. Herder, 1937)]:

The Father begetting, the Son begotten, and the Holy Ghost proceeding; consubstantial and coequal, co-omnipotent and coeternal, the one principle of the universe, Creator of all things invisible and visible, spiritual and corporeal, who from the beginning of time and by His omnipotent power made from nothing creatures both spiritual and corporeal, angelic, namely, and mundane, and then human, as it were, common, composed of spirit and body.

Man's animality, then, is part of his nature and is intended by God. Thus theologians naturally ask about the significance of aspects of being human that man has in common with the beasts. For instance, in Summa theologiae I, q. 98, a. 2, Aquinas addresses the question of whether human beings would have reproduced via sexual intercourse in a world without sin. He answers that they would have because this is proper to man's animality. One of the objections is that man becomes like the beasts in the act of intercourse and that, therefore, this would not have happened in a sinless state.

Aquinas replies (Summa theologiae I, q. 98, a. 2, ad 3):

Beasts are without reason. In this way man becomes, as it were, like them in coition, because he cannot moderate concupiscence. In the state of innocence nothing of this kind would have happened that was not regulated by reason, not because delight of sense was less, as some say (rather indeed would sensible delight have been the greater in proportion to the greater purity of nature and the greater sensibility of the body), but because the force of concupiscence would not have so inordinately thrown itself into such pleasure, being curbed by reason, whose place it is not to lessen sensual pleasure, but to prevent the force of concupiscence from cleaving to it immoderately. By "immoderately" I mean going beyond the bounds of reason, as a sober person does not take less pleasure in food taken in moderation than the glutton, but his concupiscence lingers less in such pleasures.

In other words, what man has in common with other animals does not detract from human dignity unless its specifically human determination is violated. It is irrationality that detracts from rational animality, not animality per se.

Man's body at the resurrection

In City of God, XXII, chap. 24 [trans. Dods], Augustine compares man's body, which will rise, to that of the beasts:

Moreover, even in the body, though it dies like that of the beasts, and is in many ways weaker than theirs, what goodness of God, what providence of the great Creator, is apparent! The organs of sense and the rest of the members, are not they so placed, the appearance, and form, and stature of the body as a whole, is it not so fashioned, as to indicate that it was made for the service of a reasonable soul? Man has not been created stooping towards the earth, like the irrational animals; but his bodily form, erect and looking heavenwards, admonishes him to mind the things that are above. Then the marvellous nimbleness which has been given to the tongue and the hands, fitting them to speak, and write, and execute so many duties, and practise so many arts, does it not prove the excellence of the soul for which such an assistant was provided? And even apart from its adaptation to the work required of it, there is such a symmetry in its various parts, and so beautiful a proportion maintained, that one is at a loss to decide whether, in creating the body, greater regard was paid to utility or to beauty. Assuredly no part of the body has been created for the sake of utility which does not also contribute something to its beauty. And this would be all the more apparent, if we knew more precisely how all its parts are connected and adapted to one another, and were not limited in our observations to what appears on the surface; for as to what is covered up and hidden from our view, the intricate web of veins and nerves, the vital parts of all that lies under the skin, no one can discover it. For although, with a cruel zeal for science, some medical men, who are called anatomists, have dissected the bodies of the dead, and sometimes even of sick persons who died under their knives, and have inhumanly pried into the secrets of the human body to learn the nature of the disease and its exact seat, and how it might be cured, yet those relations of which I speak, and which form the concord, or, as the Greeks call it, "harmony," of the whole body outside and in, as of some instrument, no one has been able to discover, because no one has been audacious enough to seek for them. But if these could be known, then even the inward parts, which seem to have no beauty, would so delight us with their exquisite fitness, as to afford a profounder satisfaction to the mind — and the eyes are but its ministers — than the obvious beauty which gratifies the eye. There are some things, too, which have such a place in the body, that they obviously serve no useful purpose, but are solely for beauty, as e.g. the teats on a man's breast, or the beard on his face; for that this is for ornament, and not for protection, is proved by the bare faces of women, who ought rather, as the weaker sex, to enjoy such a defense. If, therefore, of all those members which are exposed to our view, there is certainly not one in which beauty is sacrificed to utility, while there are some which serve no purpose but only beauty, I think it can readily be concluded that in the creation of the human body comeliness was more regarded than necessity. In truth, necessity is a transitory thing; and the time is coming when we shall enjoy one another's beauty without any lust — a condition which will specially redound to the praise of the Creator, who, as it is said in the psalm, has "put on praise and comeliness."

Augustine explicitly regards the human body as more beautiful than those of beasts, whereas Aquinas's explanation for the arrangment of the human body is based primarily on man's rationality and the kinds of organs best suited to the pursuit of rational ends: "All natural things were produced by the Divine art, and so may be called God's works of art. Now every artist intends to give to his work the best disposition; not absolutely the best, but the best as regards the proposed end; and even if this entails some defect, the artist cares not: thus, for instance, when man makes himself a saw for the purpose of cutting, he makes it of iron, which is suitable for the object in view; and he does not prefer to make it of glass, though this be a more beautiful material, because this very beauty would be an obstacle to the end he has in view. Therefore God gave to each natural being the best disposition; not absolutely so, but in the view of its proper end." (Summa theologiae I, q. 91, a. 3)

Man's dominion over other animals

Psalm 8:3–9:

When I look at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers,

the moon and the stars which thou hast established;

what is man that thou art mindful of him,

and the son of man that thou dost care for him?

Yet thou hast made him little less than God,

and dost crown him with glory and honor.

Thou hast given him dominion over the works of thy hands;

thou hast put all things under his feet,

all sheep and oxen,

and also the beasts of the field,

the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea,

whatever passes along the paths of the sea.

O LORD, our Lord,

how majestic is thy name in all the earth!

In Summa theologiae I, q. 96, a. 1, ad 2, St. Thomas suggests that if there had been no sin, man would have been a kind of providential caretaker for the other animals in a way similar to how he cares for domesticated animals even after the fall:

In the opinion of some, those animals which now are fierce and kill others, would, in that state [before the fall], have been tame, not only in regard to man, but also in regard to other animals. But this is quite unreasonable. For the nature of animals was not changed by man's sin, as if those whose nature now it is to devour the flesh of others, would then have lived on herbs, as the lion and falcon. Nor does Bede's gloss on Genesis 1:30, say that trees and herbs were given as food to all animals and birds, but to some. Thus there would have been a natural antipathy between some animals. They would not, however, on this account have been excepted from the mastership of man: as neither at present are they for that reason excepted from the mastership of God, Whose Providence has ordained all this. Of this Providence man would have been the executor, as appears even now in regard to domestic animals, since fowls are given by men as food to the trained falcon.

Historical Catholic speculations about real, non-human intelligent animals

In his great City of God (De civitate Dei), St. Augustine (354–430) considers the issue of whether seemingly non-human or semi-human intelligent animals are descended from Noah/Adam, i.e., whether they are ultimately of the same family as the rest of humanity. The question is relevant for Augustine because of the issue of original sin but even more fundamentally because of Christ the savior. Augustine wants to know whether Christ is mediator and savior for such beings. If there are dog-headed men, did Christ die for them, too?

Augustine, City of God XVI, chap. 8 (Translated by Marcus Dods. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 2. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887):

It is also asked whether we are to believe that certain monstrous races of men, spoken of in secular history, have sprung from Noah's sons, or rather, I should say, from that one man from whom they themselves were descended. [...] So, too, they tell of a race who have two feet but only one leg, and are of marvellous swiftness, though they do not bend the knee: they are called Skiopodes, because in the hot weather they lie down on their backs and shade themselves with their feet. Others are said to have no head, and their eyes in their shoulders; and other human or quasi-human races are depicted in mosaic in the harbor esplanade of Carthage, on the faith of histories of rarities. What shall I say of the Cynocephali, whose dog-like head and barking proclaim them beasts rather than men? But we are not bound to believe all we hear of these monstrosities. But whoever is anywhere born a man, that is, a rational, mortal animal, no matter what unusual appearance he presents in color, movement, sound, nor how peculiar he is in some power, part, or quality of his nature, no Christian can doubt that he springs from that one protoplast. We can distinguish the common human nature from that which is peculiar, and therefore wonderful.

The same account which is given of monstrous births in individual cases can be given of monstrous races. For God, the Creator of all, knows where and when each thing ought to be, or to have been created, because He sees the similarities and diversities which can contribute to the beauty of the whole. But He who cannot see the whole is offended by the deformity of the part, because he is blind to that which balances it, and to which it belongs. We know that men are born with more than four fingers on their hands or toes on their feet: this is a smaller matter; but far from us be the folly of supposing that the Creator mistook the number of a man's fingers, though we cannot account for the difference. And so in cases where the divergence from the rule is greater. He whose works no man justly finds fault with, knows what He has done. At Hippo-Diarrhytus there is a man whose hands are crescent-shaped, and have only two fingers each, and his feet similarly formed. If there were a race like him, it would be added to the history of the curious and wonderful. Shall we therefore deny that this man is descended from that one man who was first created?[...]

We are supposing these stories about various races who differ from one another and from us to be true; but possibly they are not: for if we were not aware that apes, and monkeys, and sphinxes are not men, but beasts, those historians would possibly describe them as races of men, and flaunt with impunity their false and vainglorious discoveries. But supposing they are men of whom these marvels are recorded, what if God has seen fit to create some races in this way, that we might not suppose that the monstrous births which appear among ourselves are the failures of that wisdom whereby He fashions the human nature, as we speak of the failure of a less perfect workman? Accordingly, it ought not to seem absurd to us, that as in individual races there are monstrous births, so in the whole race there are monstrous races. Wherefore, to conclude this question cautiously and guardedly, either these things which have been told of some races have no existence at all; or if they do exist, they are not human races; or if they are human, they are descended from Adam.

Notice the points Augustine makes:

- If there are (apparently) non-human rational animals, they are to be counted truly human

- They are descendants of Adam

- They are the work of God and God knows why he has made them the way he has, ultimately for the greater beauty of creation.

Given the overall message of City of God (the necessity of Christ, the only perfect mediator between God and man), the ultimate point of the discussion is: If there are dog-headed men (or any other kind of "monstrous race"), Christ died for their salvation.

Werewolves

A baptismal renunciation ascribed to St. Boniface (ca. 675–754) instructs the neophytes in detail about what they must put aside as "works of the devil":

Baptismal Renunciation Formula (PL 89:870) [my translation]. |

Hear, brethren, and think carefully about what you have renounced in Baptism. For you renounced the devil and all his works and all his empty show. What, then, are the devil's works? They are: pride, idolatry, envy, murder, ... putting faith in witches and false wolves ... |

It is worth noting that the expression strigas et fictos lupos credere could mean "believing in [the existence of] witches and false wolves," but it could also mean putting one's confidence in them or relying on them in practice ("putting faith" in them). (A point that Montague Summers makes in The Werewolf, His Science and Practice)

The detailed penitential manual (the Corrector or Medicus) found in the Decretum of the bishop Burchard of Worms (965–1025) describes a variety of occult beliefs and practices that Christians may have fallen into. Among the questions asked is:

Excerpt from Burchard's Decretum (PL 140:971) [my translation]. |

Have you believed what some are accustomed to believe, that those women known as "fates" [parcae] either exist or that they can do what they are believed to do, that is, when a person is born that they can destine him for their chosen purpose, which is the ability to be transformed into a wolf (which the foolishness of the common folk refers to as a "werewolf") or into some other shape whenever that person wishes? If you have believed this—which would never happen and is impossible—that the divine image be able to be transformed into another form or appearance, except by almighty God, you should do ten days on bread and water as penance. |

The possibility of the transformation of a human being into a wolf (or some other form) or of taking on a different appearance is not denied. What is denied is that this can be done apart from God.

The mainstream explanation for the possibility of such transformations is that they are the work of demons (or possibly of angels) acting either by God's permission or by his command. Thus, St. Augustine states City of God XVIII, chaps. 17–18 (Translated by Marcus Dods. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 2. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887):

Varro relates others no less incredible about that most famous sorceress Circe, who changed the companions of Ulysses into beasts, and about the Arcadians, who, by lot, swam across a certain pool, and were turned into wolves there, and lived in the deserts of that region with wild beasts like themselves. But if they never fed on human flesh for nine years, they were restored to the human form on swimming back again through the same pool. Finally, he expressly names one Demænetus, who, on tasting a boy offered up in sacrifice by the Arcadians to their god Lycæus according to their custom, was changed into a wolf, and, being restored to his proper form in the tenth year, trained himself as a pugilist, and was victorious at the Olympic games. And the same historian thinks that the epithet Lycæus was applied in Arcadia to Pan and Jupiter for no other reason than this metamorphosis of men into wolves, because it was thought it could not be wrought except by a divine power. For a wolf is called in Greek λυκὸς, from which the name Lycæus appears to be formed. He says also that the Roman Luperci were as it were sprung of the seed of these mysteries.

Perhaps our readers expect us to say something about this so great delusion wrought by the demons; and what shall we say but that men must fly out of the midst of Babylon? (Isaiah 48:20) For this prophetic precept is to be understood spiritually in this sense, that by going forward in the living God, by the steps of faith, which works by love, we must flee out of the city of this world, which is altogether a society of ungodly angels and men. Yea, the greater we see the power of the demons to be in these depths, so much the more tenaciously must we cleave to the Mediator through whom we ascend from these lowest to the highest places. For if we should say these things are not to be credited, there are not wanting even now some who would affirm that they had either heard on the best authority, or even themselves experienced, something of that kind. Indeed we ourselves, when in Italy, heard such things about a certain region there where landladies of inns, imbued with these wicked arts, were said to be in the habit of giving to such travellers as they chose, or could manage, something in a piece of cheese by which they were changed on the spot into beasts of burden, and carried whatever was necessary, and were restored to their own form when the work was done. Yet their mind did not become bestial, but remained rational and human, just as Apuleius, in the books he wrote with the title of The Golden Ass, has told, or feigned, that it happened to his own self that, on taking poison, he became an ass, while retaining his human mind.

These things are either false, or so extraordinary as to be with good reason disbelieved. But it is to be most firmly believed that Almighty God can do whatever He pleases, whether in punishing or favoring, and that the demons can accomplish nothing by their natural power (for their created being is itself angelic, although made malign by their own fault), except what He may permit, whose judgments are often hidden, but never unrighteous. And indeed the demons, if they really do such things as these on which this discussion turns, do not create real substances, but only change the appearance of things created by the true God so as to make them seem to be what they are not. I cannot therefore believe that even the body, much less the mind, can really be changed into bestial forms and lineaments by any reason, art, or power of the demons; but the phantasm of a man which even in thought or dreams goes through innumerable changes may, when the man's senses are laid asleep or overpowered, be presented to the senses of others in a corporeal form, in some indescribable way unknown to me, so that men's bodies themselves may lie somewhere, alive, indeed, yet with their senses locked up much more heavily and firmly than by sleep, while that phantasm, as it were embodied in the shape of some animal, may appear to the senses of others, and may even seem to the man himself to be changed, just as he may seem to himself in sleep to be so changed, and to bear burdens; and these burdens, if they are real substances, are borne by the demons, that men may be deceived by beholding at the same time the real substance of the burdens and the simulated bodies of the beasts of burden. For a certain man called Præstantius used to tell that it had happened to his father in his own house, that he took that poison in a piece of cheese, and lay in his bed as if sleeping, yet could by no means be aroused. But he said that after a few days he as it were woke up and related the things he had suffered as if they had been dreams, namely, that he had been made a sumpter horse, and, along with other beasts of burden, had carried provisions for the soldiers of what is called the Rhœtian Legion, because it was sent to Rhœtia. And all this was found to have taken place just as he told, yet it had seemed to him to be his own dream. And another man declared that in his own house at night, before he slept, he saw a certain philosopher, whom he knew very well, come to him and explain to him some things in the Platonic philosophy which he had previously declined to explain when asked. And when he had asked this philosopher why he did in his house what he had refused to do at home, he said, "I did not do it, but I dreamed I had done it." And thus what the one saw when sleeping was shown to the other when awake by a phantasmal image.

These things have not come to us from persons we might deem unworthy of credit, but from informants we could not suppose to be deceiving us. Therefore what men say and have committed to writing about the Arcadians being often changed into wolves by the Arcadian gods, or demons rather, and what is told in song about Circe transforming the companions of Ulysses, if they were really done, may, in my opinion, have been done in the way I have said. As for Diomede's birds, since their race is alleged to have been perpetuated by constant propagation, I believe they were not made through the metamorphosis of men, but were slyly substituted for them on their removal, just as the hind was for Iphigenia, the daughter of king Agamemnon. For juggleries of this kind could not be difficult for the demons if permitted by the judgment of God; and since that virgin was afterwards, found alive it is easy to see that a hind had been slyly substituted for her. But because the companions of Diomede were of a sudden nowhere to be seen, and afterwards could nowhere be found, being destroyed by bad avenging angels, they were believed to have been changed into those birds, which were secretly brought there from other places where such birds were, and suddenly substituted for them by fraud. But that they bring water in their beaks and sprinkle it on the temple of Diomede, and that they fawn on men of Greek race and persecute aliens, is no wonderful thing to be done by the inward influence of the demons, whose interest it is to persuade men that Diomede was made a god, and thus to beguile them into worshipping many false gods, to the great dishonor of the true God; and to serve dead men, who even in their lifetime did not truly live, with temples, altars, sacrifices, and priests, all which, when of the right kind, are due only to the one living and true God.

Following Augustine, when St. Thomas takes up the question of werewolfery, he explains (De potentia, q. 6, a. 5, ad 6 [my translation]:

The transformations [of human beings into wolves or birds, as Varro reports,] were not in truth but only in appearance, through the work of a demon by changing the bodily appearance in the human imagination, as Augustine says.

In the body of the same article of De potentia, he lays down as a general rule that demons can produce such effects in two ways, "In one way, by a true transmutation of the body, and in another way by an illusion of the senses and a change in the imagination."

Elsewhere, St. Thomas explains (De malo, q. 16, a. 9, ad 2 [my translation]:

A demon uses the active natural principle as an instrument to produce an effect. Now an instrument acts not by its own power alone but also by the power of the principal agent. And thus something can come about through an instrument that is beyond the the instrument's power considered absolutely, as a bed is made through a saw by the power of the craftsman. And likewise, through the active natural principles that they use for effects, demons can do certain things beyond the natural power of the agents, but not converting the shape of the human body into that of a beast in truth, since this is apart from the order implanted in nature by God. Instead, all the aforementioned conversions happened in imaginary appearance rather than in truth, as Augustine makes clear in that passage.

A particularly interesting account is that of the Ossory werewolves. One full report is found in the the Topographia Hibernica of Giraldus Cambrensis (1146–1223), who narrates the story of a priest who runs into a talking wolf. The wolf then explains to the priest that he and his companion are actually human beings and, in fact, Catholics. The priest verifies this by asking the wolf basic catechism questions. The wolf then leads the priest to his companion, a female wolf (actually a woman) who is seriously ill. The priest administers the last rites to her and then gives a full report to the bishop, who in turn informs the Holy See.

The priest gives Holy Communion to one of the Ossory werewolves, who lies seriously ill.

As one would expect, Giraldus Cambrensis comments on the possibility of the event with reference to Augustine, i.e., that demons can indeed produce such effects when God permits it but that they cannot really change the natures of things. In other words, they can produce a change in appearance (so that a man seems to be a wolf in all externals), but they cannot actually change a man into a wolf. After repeating that only God can truly change one nature into another (e.g., water into wine), Giraldus concludes his commentary in this way (Topographia Hibernica, d. 2, chap. 19 (ed. Dimock, p. 107) [my translation]:

But as to that specific change of bread into Christ's body—not only a specific change but, in fact a substantial one, since while the whole species remains the substance alone is changed—I have thought it safer not to get into the question here. For its makeup is far above human understanding, very deep, and difficult.

Talking-animals in lore, amusement, and mockery